The ptetools package compartmentalizes the steps needed

to implement estimators of group-time average treatment effects (and

their aggregations) in order to make it easier to apply the same sorts

of arguments outside of their “birthplace” in the literature on

difference-in-differences.

Essentially, the idea is that many panel data causal inference problems involve steps such as:

Defining an identification strategy (e.g., difference-in-differences)

Defining a notion of a group (e.g., based on treatment timing)

Looping over groups and time periods

Organizing the data so that the correct data show up for each group and time period

Computing group-time average treatment effects (or other parameters that are local to a group and a time period)

Aggregating group-time average treatment effect parameters (e.g., into an event study or an overall average treatment effect parameter)

Many of these steps are common across different panel data causal inference settings. For example, you could implement a difference-in-differences identification strategy or a change-in-changes identification strategy with all of the same steps as above except for replacing step 1.

The idea of the ptetools package is to re-use as much

code/infrastructure as possible when developing new approaches to panel

data causal inference. For example, ptetools sits as the

“backend” for several other packages including: ife,

contdid, and parts of qte.

The main function is called pte. The most important

parameters that it takes in are subset_fun and

attgt_fun. These are functions that the user should pass to

pte.

subset_fun takes in the overall data, a group, a time

period, and possibly other arguments and returns a

data.frame containing the relevant subset of the data, an

outcome, and whether or not a unit should be considered to be in the

treated or comparison group for that group/time. There is one example of

a relevant subset function provided in the package: the

two_by_two_subset function. This function takes an

original dataset, subsets it into pre- and post-treatment periods and

denotes treated and untreated units. This particular subset is perhaps

the most common/important one for thinking about treatment effects with

panel data, and this function can be reused across applications.

The other main function is attgt_fun. This function

should be able to take in the correct subset of data, possibly along

with other arguments to the function, and report an ATT for

that subset. With minor modification, this function should be available

for most any sort of treatment effects application — for example, if you

can solve the baseline 2x2 case in difference in differences, you should

use that function here, and the ptetools package will take

care of dealing with the variation in treatment timing.

If attgt_fun returns an influence function, then the

ptetools package will also conduct inference using the

multiplier bootstrap (which is fast) and produce uniform confidence

bands (which adjust for multiple testing).

The default output of pte is an overall treatment effect

on the treated (i.e., across all groups that participate in the

treatment in any time period) and and event study. More aggregations are

possible, but these seem to be the leading cases; aggregations of

group-time average treatment effects are discussed at length in Callaway and

Sant’Anna (2021).

Below are several examples of how the ptetools package

can be used to implement an identification strategy with a very small

amount of new code.

The did

package, which is based on Callaway and

Sant’Anna (2021), includes estimates of group-time average treatment

effects, ATT(g,t), based on a difference in differences

identification strategy. The following example demonstrates that it is

easy to compute group-time average treatment effects using difference in

differences using the ptetools package. [Note:

This is definitely not the recommended way of doing this as there is

very little error handling, etc. here, but it is rather a proof of

concept. You should use the did package for this case.]

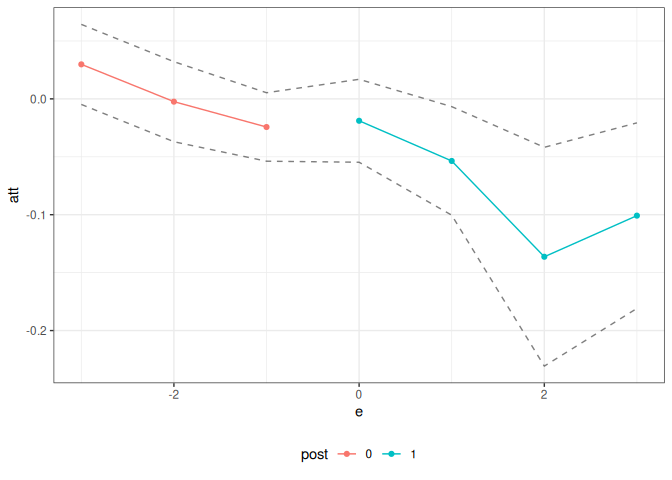

This example reproduces DID estimates of the effect of the minimum

wage on employment using data from the did package.

library(did)

data(mpdta)

did_res <- pte(

yname = "lemp",

gname = "first.treat",

tname = "year",

idname = "countyreal",

data = mpdta,

setup_pte_fun = setup_pte,

subset_fun = two_by_two_subset,

attgt_fun = did_attgt,

xformla = ~lpop

)

summary(did_res)

#>

#> Overall ATT:

#> ATT Std. Error [ 95% Conf. Int.]

#> -0.0305 0.013 -0.056 -0.0049 *

#>

#>

#> Dynamic Effects:

#> Event Time Estimate Std. Error [95% Conf. Band]

#> -3 0.0298 0.0143 -0.0048 0.0643

#> -2 -0.0024 0.0142 -0.0370 0.0321

#> -1 -0.0243 0.0122 -0.0538 0.0053

#> 0 -0.0189 0.0148 -0.0547 0.0169

#> 1 -0.0536 0.0193 -0.1004 -0.0067 *

#> 2 -0.1363 0.0390 -0.2307 -0.0418 *

#> 3 -0.1008 0.0331 -0.1809 -0.0207 *

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: `*' confidence band does not cover 0

ggpte(did_res)

What’s most interesting here, is that the only “new” code that needs

to be write is in the

did_attgt function. You will see that this is a very

small amount of code.

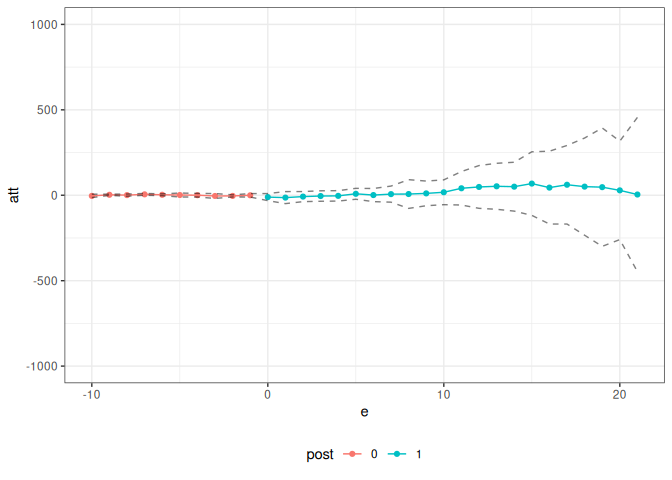

As a next example, consider trying to estimate effects of COVID-19 related policies during a pandemic. The estimates below are for the effects of state-level shelter-in-place orders during the early part of the pandemic.

The data for this example comes from the ppe package

which can be loaded by running

devtools::install_github("bcallaway11/ppe")

library(ppe)

data(covid_data)Callaway and Li (2021) argue that a particular unconfoundedness-type strategy is more appropriate in this context than DID-type strategies due to the spread of COVID-19 cases being highly nonlinear. However, they still deal with the challenge of variation in treatment timing. Therefore, it is still useful to think about group-time average treatment effects, but the DID strategy should be replaced with their particular unconfoundedness type assumption.

The ptetools package is particularly useful here.

# formula for covariates

xformla <- ~ current + I(current^2) + region + totalTestResultscovid_res <- pte(

yname = "positive",

gname = "group",

tname = "time.period",

idname = "state_id",

data = covid_data2,

setup_pte_fun = setup_pte_basic,

subset_fun = two_by_two_subset,

attgt_fun = covid_attgt,

xformla = xformla,

max_e = 21,

min_e = -10

)

summary(covid_res)

#>

#> Overall ATT:

#> ATT Std. Error [ 95% Conf. Int.]

#> 14.8882 76.5819 -135.2096 164.9859

#>

#>

#> Dynamic Effects:

#> Event Time Estimate Std. Error [95% Conf. Band]

#> -10 -3.7266 3.7443 -13.6824 6.2291

#> -9 2.6607 1.3125 -0.8292 6.1505

#> -8 0.8290 2.4008 -5.5547 7.2126

#> -7 5.2843 2.0354 -0.1277 10.6964

#> -6 2.8555 1.9891 -2.4335 8.1445

#> -5 1.3589 4.3728 -10.2680 12.9859

#> -4 0.3294 3.9515 -10.1774 10.8361

#> -3 -4.2227 5.3801 -18.5279 10.0825

#> -2 -3.8447 2.3510 -10.0960 2.4065

#> -1 -0.2234 3.8195 -10.3790 9.9323

#> 0 -10.8156 7.8065 -31.5725 9.9412

#> 1 -13.7998 13.2360 -48.9935 21.3939

#> 2 -7.8432 11.1086 -37.3801 21.6938

#> 3 -4.5541 11.5184 -35.1808 26.0725

#> 4 -3.5368 11.4626 -34.0151 26.9415

#> 5 8.5221 12.0109 -23.4141 40.4583

#> 6 1.1140 14.4510 -37.3100 39.5380

#> 7 6.6384 17.7043 -40.4361 53.7130

#> 8 7.1288 31.6224 -76.9530 91.2106

#> 9 10.8758 27.1430 -61.2955 83.0471

#> 10 17.5057 27.3018 -55.0877 90.0991

#> 11 40.8318 36.8285 -57.0926 138.7561

#> 12 48.6134 47.0816 -76.5730 173.7998

#> 13 52.4228 50.6093 -82.1436 186.9892

#> 14 50.2000 53.7874 -92.8168 193.2169

#> 15 68.2960 69.9730 -117.7571 254.3491

#> 16 44.7305 80.1319 -168.3345 257.7955

#> 17 61.4670 86.4689 -168.4476 291.3815

#> 18 50.4635 106.9963 -234.0318 334.9589

#> 19 47.3392 130.2984 -299.1149 393.7933

#> 20 28.6326 108.3420 -259.4409 316.7061

#> 21 4.3445 169.7318 -446.9601 455.6491

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: `*' confidence band does not cover 0

ggpte(covid_res) + ylim(c(-1000, 1000))

What’s most interesting is just how little code needs to be written

here. The only new code required is the ppe::covid_attgt

function which is available

here, and, as you can see, this is very simple.

The code above used the multiplier bootstrap. The great thing about the multiplier bootstrap is that it’s fast. But in order to use it, you have to work out the influence function for the estimator of ATT(g,t). Although I pretty much always end up doing this, it can be tedious, and it can be nice to get a working version of the code for a project going before working out the details on the influence function.

The ptetools package can be used with the empirical

bootstrap. There are a few limitations. First, it’s going to be

substantially slower. Second, this code just reports pointwise

confidence intervals. However, this basically is set up to fit into my

typical workflow, and I see this as a way to get preliminary

results.

Let’s demonstrate it. To do this, consider the same setup as in Example 1, but where no influence function is returned. Let’s write the code for this:

# did with no influence function

did_attgt_noif <- function(gt_data, xformla, ...) {

# call original function

did_gt <- did_attgt(gt_data, xformla, ...)

# remove influence function

did_gt$inf_func <- NULL

did_gt

}Now, we can show the same sorts of results as above

did_res_noif <- pte(

yname = "lemp",

gname = "first.treat",

tname = "year",

idname = "countyreal",

data = mpdta,

setup_pte_fun = setup_pte,

subset_fun = two_by_two_subset,

attgt_fun = did_attgt_noif, # this is only diff.

xformla = ~lpop

)

summary(did_res_noif)

#>

#> Overall ATT:

#> ATT Std. Error [ 95% Conf. Int.]

#> -0.0323 0.0128 -0.0574 -0.0071 *

#>

#>

#> Dynamic Effects:

#> Event Time Estimate Std. Error [95% Pointwise Conf. Band]

#> -3 0.0269 0.0110 0.0053 0.0485 *

#> -2 -0.0050 0.0133 -0.0311 0.0211

#> -1 -0.0229 0.0152 -0.0526 0.0069

#> 0 -0.0201 0.0124 -0.0445 0.0042

#> 1 -0.0547 0.0166 -0.0872 -0.0222 *

#> 2 -0.1382 0.0372 -0.2111 -0.0653 *

#> 3 -0.1069 0.0392 -0.1836 -0.0302 *

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: `*' confidence band does not cover 0

ggpte(did_res_noif)

What’s exciting about this is just how little new code needs to be written.